The safest investment in the world is U.S. Treasury bonds. The reason is simple: Uncle Sam can’t default on his obligations, because he can print the money to pay them.

Ironically, however, you can rack up serious losses in all kinds of bonds, including the world’s safest. Which brings us to this week’s reader question.

I’ve put a bunch of money into U.S. Treasury bond mutual funds in my 401(k). I’ve been checking my statements recently and they show losses in these funds. Will I recover the value? How does this happen? I don’t get it.

– Karen

This reader owns a fund that invests in U.S. Treasury bonds. But if you own any kind of bond or bond mutual fund, you really need to understand how they work and the potential for risk, especially now that interest rates are starting to rise.

If you think you don’t own any bonds, be aware that if you own a mutual fund within your 401(k) or other retirement plan that has the word “income” or “balanced” in the title, odds are you own some bonds. The way to find out for sure is to do a web search for the exact title of your fund, followed by the word “prospectus.” Then check out the prospectus and see what the fund invests in.

Now, let’s take a closer look at exactly what a bond is and how they work.

The simplest explanation of bonds you’ll ever read

While it may seem as if there are hundreds of different potential investments in the world, the vast majority fall into only two categories:

- Loaner: You lend money to someone and they promise to pay it back at some future date, along with some interest. Typical loaner investments include certificates of deposit and all types of bonds.

- Owner: You own part of a company, typically in the form of stock. There’s no set interest rate, no maturity date and no guarantee you’ll get your money back.

And while it may seem as if there are infinite investing risks, there are basically only two:

- Default risk: The company you invest in goes bankrupt and you lose your money.

- Market risk: The stock or bond you invest in declines in value and you sell it.

U.S. Treasury bonds are loaner investments. As I said above, they have virtually no default risk, because the government can simply print the money to pay its debts. But from the time they’re issued until the day they mature, which could be as long as 30 years, Treasury bonds fluctuate in value. In short, they have market risk.

What makes bonds go up and down in value?

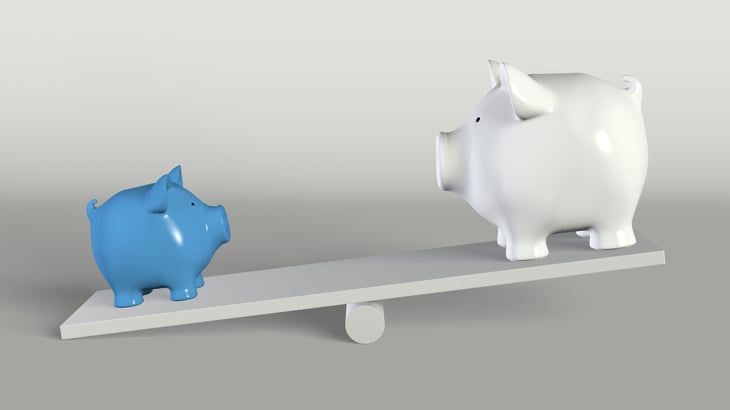

If you’re willing to wait until U.S. Treasury bonds mature, you’ll always get the face amount; e.g., if you buy a $1,000 bond, you’ll get $1,000 when it comes due. But between now and then, prices can change. To understand why, imagine a seesaw.

On one end of the seesaw are bond prices. On the other are interest rates. If interest rates rise, bond prices fall. If rates fall, bond prices rise.

To use fancy terms, bond prices are inversely correlated to interest rates.

Why is this? Well, imagine last year I put $1,000 into a 10-year Treasury bond with an interest rate of 1 percent. But today interest rates have risen and now identical 10-year bonds are being offered with a rate of 2 percent. Since anyone would rather earn 2 percent than 1 percent, nobody is going to give me $1,000 for a bond that pays 1 percent. So if I wanted to sell my bond today, I’d have to sell it for less than I paid for it. My bond’s value went down because interest rates went up.

My bond is still going to be worth $1,000 when it matures years from now. But if I need to sell it today? Nope. Something else to know: The longer it is until the bond matures, the more it will drop in value if rates rise.

Now let’s go from classroom to the real world for a demonstration.

During the month of November, interest rates went up a bunch. (For an explanation of why, see this recent article.) On Nov. 1, 10-year treasury bonds paid 1.83 percent interest. At the end of the month, on Nov. 30, they were paying 2.39 percent. While that may not seem like much, that half percent rate increase is rare, and it’s a big deal. So how did this rate move impact the prices of real-life bond funds?

Let’s use Vanguard U.S. Treasury funds as an example and see what happened. Here’s the November performance of Vanguard short-term, intermediate-term and long-term Treasury bond mutual funds.

- Short-term Treasury fund: Down 0.8 percent

- Intermediate-term Treasury fund: Down 3 percent

- Long-term Treasury fund: Down 8 percent

So the long term bond fund lost 8 percent of its value in just one month, 10 times more than the short-term fund lost. This is a textbook example of how rising rates can hurt bond prices, especially when those bonds are long-term ones.

If the value of my fund drops, will it come back over time?

Karen is rightfully concerned that her bond fund has decreased in value. But shouldn’t it come back? After all, I just explained that while bonds may fluctuate in value, they mature at face value. That means any losses showing on her statement between now and then are only temporary.

Or are they?

It’s true that if you hold a single bond until it matures, you should get your principal back. But a bond mutual fund isn’t a single bond. It’s a vast portfolio of bonds, with a manager who’s likely buying and selling. Whenever a bond within that portfolio is bought or sold, it could be at a profit or loss.

So while a U.S. Treasury fund like Karen’s removes the default risk, a manager who’s buying and selling bonds is still taking market risk. And that market risk could translate into real, as opposed to paper, profits or losses.

Rates are rising … should I panic?

When the stock market was cut in half back in 2008-2009, it ruined lives. People lost jobs. 401(k)s were decimated. Many on the verge of retirement were forced to stay in the workplace to make up their losses.

And many of those afraid of stocks probably turned to bonds, assuming them to be a safer alternative. They were right, as long as interest rates didn’t dramatically rise, which they still haven’t.

Next week, the Federal Reserve will probably raise the rate they directly control, called the discount rate, by a quarter-percent. This will be the second time they’ve raised: the first was last year. This much-anticipated rate hike will ripple through the economy, showing up in everything from credit card rates to bond prices. While it’s not a big increase, for those invested in long-term bonds or bond mutual funds, it’s a shot across the bow.

Time to panic? No. Because economic growth is still tepid, the Fed won’t raise rates rapidly, and individual increases will most likely be like the one we’re likely to have next week: minuscule. That being said, market interest rates change all the time. Note that the 10-year Treasury rate gained a half-percent in November: Wall Street bond traders did that, not the Fed.

Suffice to say that if rates keep rising, a long-term bond fund will be an unpleasant place to be.

Which begs the question …

What’s an investor to do?

It’s always best to diversify. Use mutual funds to own some stocks, some short-term bonds, some long-term bonds, some money market funds. Very few people can successfully time things like bull markets and interest rate changes, so spreading your investments around is always a good idea.

That being said, while rates are unlikely to rise a lot in the coming months, the path of least resistance is now up. This should come as no surprise. The Fed Funds rate has been near zero since 2006. It really had no place to go but up. It was just a matter of when.

But the playing field has now changed. And that leaves you with two options: Adjust your portfolio or adjust your expectations.

If you’re concerned about rising rates hurting your long-term bond mutual fund, adjust your portfolio by switching to intermediate or short-term funds. They won’t pay as much in interest, but if rates rise rapidly, as you’ve seen, they’re a lot more likely to preserve principal.

If you’re happy with your current investment mix and want to keep money in long-term bond funds, adjust your expectations by mentally preparing for potential paper losses as rates rise.

A final option is to avoid bond mutual funds and buy only actual bonds. Then you know that if you hold your bond to maturity, you’ll get the face value. But owning bonds typically takes more money than owning funds, and individual bonds aren’t an option in a 401(k).

What’s your exposure to bonds? Are you adjusting your holdings in light of likely interest rate increases? Share with us in comments below or on our Facebook page.

Got a question you’d like answered?

You can ask a question simply by hitting “reply” to our email newsletter. If you’re not subscribed, fix that right now by clicking here. The questions I’m likeliest to answer are those that will interest other readers. In other words, don’t ask for super-specific advice that applies only to you. And if I don’t get to your question, promise not to hate me. I do my best, but I get a lot more questions than I have time to answer.

About me

I founded Money Talks News in 1991. I’m a CPA, and have also earned licenses in stocks, commodities, options principal, mutual funds, life insurance, securities supervisor and real estate. If you’ve got some time to kill, you can learn more about me here.

Got more money questions? Browse lots more Ask Stacy answers here.

Add a Comment

Our Policy: We welcome relevant and respectful comments in order to foster healthy and informative discussions. All other comments may be removed. Comments with links are automatically held for moderation.