Everyone wants to protect the health of their pet. But does health insurance really payoff? Not for every dog or cat. But a close look at the numbers suggests it can make sense for owners with big hearts and deep pockets.

Americans spend more than $1.5 billion a year on pet insurance, a figure that’s been growing by at least 15% a year, according to an industry group.

If you’ve researched pet insurance, you already know that policies don’t come cheap. Monthly premiums typically run to $50 or so for a dog, and $30 for a cat — and the lifetime cost can easily top $5,000 and $3,000, respectively.

That’s why we decided to take a closer look at the benefits of all that spending for pet owners, and whether they’re enough to justify the cost.

To do that, we gathered price quotes from four pet insurers for both purebred and mixed-breed dogs and cats over eight years of their lives, since prices go up sharply for very old pets. We compared the prices against probable vets’ bills, as reported by the American Pet Products Association and vets we contacted.

And to come up with a comprehensive answer we considered what you’d pay for a pet that enjoys normal medical life, with its occasional but not life-threatening illnesses and accidents, and a worst-case scenario in which a pet develops a serious and costly condition.

Our number-crunching confirmed that the odds are against ever collecting on insurance on a “normal pet.” Rather, like most insurance, a pet policy is mostly a hedge against the worst happening.

Whether a policy makes sense for you, then, will largely depend on the kind of pet owner you are. In particular, whether, when an animal gets seriously ill and vet bills climb into the thousands of dollars, you’re inclined to take every step to prolong your pet’s life, or are comfortable letting it go.

Here’s when pet insurance will work the best for you.

A policy probably won’t pay off over a normal medical life

If your dog or cat suffers a typical array of medical issues, you’ll pay premiums and get little to nothing in return, at least in financial terms. That’s partly because the Accident and Illness policies most people buy, and that we used in our analysis, don’t cover routine care such as wellness checks, vaccines and parasite preventatives.

This limited value is hardly unique to pet insurance. After all, many or most people pay a lifetime of premiums on their homeowners and car policies, yet rarely if ever make a claim on them. The coverage is there mostly in case your home is gutted by fire or your car is totaled in a crash.

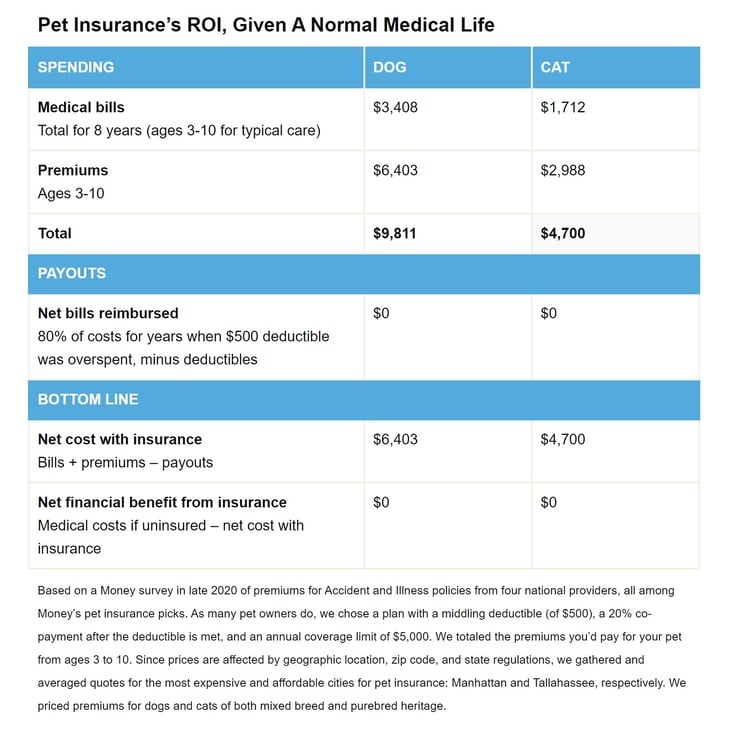

The chart below shows the costs and benefits of insuring dogs and cats that run up average bills between ages three to 10.

That’s a range that skips the puppy years but kicks in before most serious conditions develop, which could preclude getting coverage, and before old age sends premiums skyrocketing (rising by an average of about half for dogs and a third for cats between ages eight and 10, according to our 2020 price survey).

The annual U.S. averages for vets’ bills ($426 for dogs, $214 for cats, according to the American Pet Products Association) are less than the typical $500 deductible of many pet policies (including those we used in our pricing). That’s why the odds are against ever collecting on insurance on a “normal pet.”

A major ‘medical event’ increases the odds

Pet insurance is most advantageous financially when your dog or cat gets really sick — as in getting cancer, a predominant serious illness for both species, or cranial cruciate injury, a knee condition common to some dog breeds.

While it’s statistically unlikely they’ll develop such a condition, the bills if they do could easily run to four- or five figures, and pet insurance would pay most of that cost.

For example, either chemotherapy or radiation treatment can easily cost $6,000 to $7,000, according to Cornell College of Veterinary Medicine, and that’s not including the bills for diagnosis and follow-up treatments that can add thousands of dollars more. (Money writer Ingrid Case racked up bills of $28,000 in treating cancer in her St. Barnard.)

Disease or other conditions are not the only potential cause of major expense for your pet, of course.

There are run-ins with cars and self-inflicted injuries — such as what Steve Weinrauch, Trupanion’s chief veterinary officer and chief product officer, identifies as the tendency of Labradors, to eat “silly things,” from rocks to socks, and require expensive surgery to remove those items.

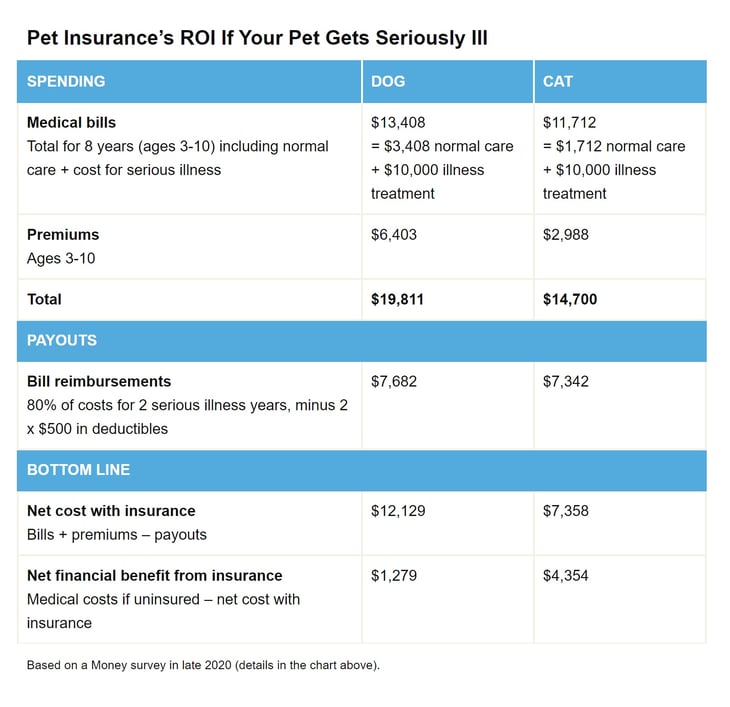

The policy we priced will pay 80% of medical bills, a popular level. But that leaves you to cover the remaining 20% of bills. You also pay a deductible ($500 for the policies we priced) in any year when spending exceeds that level, as we calculated it would during two years of treatment for the pet’s serious condition.

There is, however, a gap between dogs and cats in how well policies pay off when the pet gets very ill. The economics are notably better for a cat — which might be surprising, given that both vets’ bills and insurance premiums are generally lower for felines.

A key reason for the gap is that treating cancer and some other serious conditions isn’t notably cheaper for a cat than a dog. That and lower premiums for cats compared with dogs mean you’ll net more than three times as much in insurance reimbursements for a cat with cancer as for a dog that’s similarly stricken.

Getting a lot from a policy means spending a lot, too

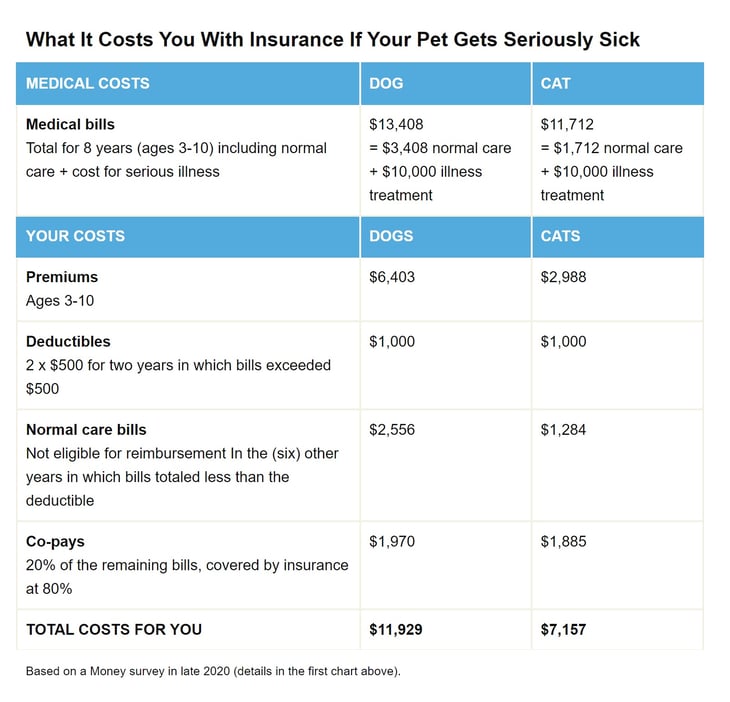

If your pet suffers a catastrophic medical problem, the insurance company will spend big — but so will you.

For a medical bill of $10,000 or more — an entirely plausible range to treat cancer or for multiple operations after a serious accident — your costs could easily run to the thousands of dollars. That’s because you’d be responsible (depending on the policy you choose) for a copay of 10%, 20%, or 30% of the total bills for treatment.

What’s more, you’d have to come up with the entire treatment cost upon completion of the care. Where human health insurance usually reimburses the medical provider directly, pet insurance requires you to pay the entire bill for your animal’s care up front, and then wait for reimbursement from the insurer.

In addition to all this, annual caps on coverage might deprive you on some reimbursement during certain years.

Again, unlike most human health insurance, a pet policy has an annual payment limit that you select, with higher limits triggering higher premiums. The typical cap is $5,000. While that amount should suffice in any normal year, it might be short of what you need in an unlucky year of multiple surgeries or extended chemotherapy.

There are also lifetime limits on payments, which you might hit were your pet to have prolonged or recurring treatments.

To insure or not to insure?

Pets aren’t people, but to many of us they’re family, not mere companions or items of property. That honorary human status can complicate decisions over pet care, including whether to pay for health insurance for furry family members.

The prime candidates for pet insurance are people who truly treat their pets as they might any human loved one, and are prepared to do it all to save a pet.

So are people who prefer to minimize making agonizing choices about expensive pet care. Without insurance, every potential medical treatment for your pet demands an individual decision on its cost versus its benefits. Investing in pet insurance limits the decision-making.

You even have an incentive to visit the vet more often and, at the first signs of medical trouble, then be on the hook for no more than a percentage of the bill, assuming you’ve met the deductible for the year.

As we noted earlier, though, the deductibles and copays for serious treatment can be seriously large. Don’t buy a policy without being ready and able to pony up a significant sum when the worst happens, medically speaking. You may be better off financially not to insure if you’re likely to pass on expensive treatment because you can’t or won’t come up with the copays.

You can reduce copays by opting for a policy that makes them 10%, say, rather than the popular 20% or 30% levels. You’ll pay relatively little — perhaps $50 more a year — to get a policy with a 10% copay rather than one with a 20% one.

It’s also worthwhile is to shop around for policies. Our pet-insurance price survey last year found some insurers charged double what others did. That difference could amount to hundreds of dollars and year, and thousands over the pet’s lifetime — and potentially change your decision on whether or not to insure.

Price research: Fernando Garcia Delgado

© Copyright 2020 Ad Practitioners, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

This article originally appeared on Money.com and may contain affiliate links for which Money receives compensation. Opinions expressed in this article are the author’s alone, not those of a third-party entity, and have not been reviewed, approved, or otherwise endorsed. Offers may be subject to change without notice. For more information, read Money’s full disclaimer.

Add a Comment

Our Policy: We welcome relevant and respectful comments in order to foster healthy and informative discussions. All other comments may be removed. Comments with links are automatically held for moderation.